Late Blow

LTMC - Safety Policy

LTMC - Additives and Food Safety Policy

LTMC - Unexplained Textures, Official Policy

These documents, and more, are in the "Files" and "Announcements" zones at these links ...

The four RRRRs of cheese making ...

Re-Read Recipe before Rennet.

Boil all pots, utensils, cheesecloths, etc. before making cheeses.

Pasteurise your brine to ensure there is no b.linens (unless you want a stinky cheese).

Rinse anti-bacterial detergents thoroughly to avoid killing wanted bacteria.

Books and Videos random order.

The Art of Natural Cheesemaking: The World's Best Cheeses - David Asher

Cheese Please!: A guide to the therapy of cheesemaking at home - Tracey Johnson

200 Easy Home-made Cheese Recipes - Debra Amrein-Boyes

Keep Calm And Make Cheese - Gavin Webber

Gavin Webber's YouTube Videos - mostly metric units

Cheese52 Videos - mostly USA style units

Recipes - Don't Panic

Historically cheese was made without digital scales, thermometers and pH meters. So don't panic if your measurements are a little bit off. You'll still get cheese. It's possible to recover from some epic mistakes. My recipe said to ripen the milk for 90 minutes. I left the gas burner on and boiled the milk for 90 minutes. My solution was to add citric acid and the milk curdled very well. I cooled it to 32 Celsius and re-added mesophilic bacteria and Penicillium candidum. The curds went into small moulds. One week later I had bloomy wheels rather like Camembert. After a further week of ripening at 12 Celsius they were very acceptable. The texture was pleasant but not authentic.

Unit Conversions

Your recipe may forget to mention if it's Imperial, USA or Metric.

Temperatures may be in Celsius or Fahrenheit.

Social media posts often fail to indicate the measurement units.

My inner Physics teacher despairs.

Napoleon got one thing right. We should all standardise on the same system of units.

Imperial and USA pints, quarts and gallons are similar.

Assuming the wrong system might alter but not ruin a cheese.

Celsius and Fahrenheit are drastically different and getting this wrong will ruin the cheese.

Tips

Bacteria

Brevibacterium linens - Stinky. Washed-rind and smear-ripened red mould cheeses. Limburger and Port-Salut. Aroma attracts mosquitoes.

Propionibacterium shermanii - This makes eyes or the holes. This produces bubbles of CO2.

Bacteria (Mesophiles) - Acidify the milk at 18°C to 32°C for up to 24 hours.

Lactobacillus acidophilus - Flavour, texture, and proteolysis (protein softening while ripening.)

Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus - Converts lactose sugar into lactic acid and acetaldehyde yogurt aroma.

Lactobacillus helveticus - Reduce bitterness and produce nutty flavours typical in Swiss cheeses.

Lactococcus lactis subsp. biovar diacetylactis - Buttery taste and texture. Produce lactic acid, diacetyl and CO2

Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris - One of the two commonest milk ripening bacteria.

Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis - One of the two commonest milk ripening bacteria.

Leuconostoc mesenteroides subsp. cremoris - Produces gas bubbles, and flavour compounds.

Bacteria (Thermophiles) - Acidify the milk at over 32°C for up to 24 hours. 42°C optimum for yogurt.

Streptococcus thermophilus - Used to make yogurt by turning lactose, the sugar in milk, into lactic acid.

Bacterial starters on a budget - bacteria and moulds are expensive to buy.

Live Yogurt - contains thermophilic bacteria and can be used as a low cost starter.

Live Cultured Buttermilk - contains mesophilic bacteria and can be used as a low cost starter.

Bifidobacterium Yogurt Starter

Contains:

Lactobacillus delbrueckii

Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris

Bifidobacterium Lactis

Leuconostoc mesenteroides subsp. mesenteroides

Streptococcus thermophilus

Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis biovar diacetylactis

Lactobacillus acidophilus

Lactobacillus lactis subsp.lactis

Lactobacillus casei

Lactobacillus rhamnosus.

Filmjölk - Useful combination of cultures!

Lactococcus lactis

Lactococcus lactis cremoris

Lactococcus lactis diacetylactis, Leuconostoc mesenteroides cremoris.

Leuconostoc mesenteroides cremoris.

Live Kefir

This contains both mesophilic and thermophilic bacteria and can be used as a starter.

The ripening temperature determines which type dominates.

Around 22 to 32°C, mesophilic will dominate.

Around 42°C, thermophilic will dominate.

Kefir contains other bacteria, moulds and yeasts, harmless or beneficial in cheese making.

Quantity to Use - no need to be super precise

Use a 1/4 cup to start a gallon or 60 ml to start 4 litres.

Avoid using a lot more starter. I've had problems with wet slimy curds that are hard to dry.

Don't wait too long before adding rennet. You don't want the milk to start curdling before the rennet is added.

Calcium Chloride

Adds calcium back into milk that has been pasteurised. This gives stronger curds.

It's not usually needed for raw milk or mozzarella.

Using too much gives a bitter taste.

Dry CaCl2 is likely to get damp so it's safer to store a 30% solution. 70 grams of boiled water to 30 grams of CaCl2.

CAUTION:

Mix slowly as it gets hot while it's dissolving.

Use a suitable container.

Add the powder to the water gradually.

It has an indefinite shelf life.

Keep it in the fridge in a sealed container to prevent evaporation of the water.

CaCl2 is also marketed as Pickle Crisp.

Cave Storage

Temperature

Many cheeses don't need cave storage. Brie, Camembert and blues will ripen rather slowly in a normal fridge. Fresh cheeses don't need any ripening. The best temperature for a cheese cave is around 12°C. Wine fridges can be used as they are set to around this temperature. Any fridge or freezer can be used with a separate temperature controller. Search for Inkbird on Google for examples of temperature controllers. Cheaper options are available if you can do a bit of wiring up.

Humidity

Inkbird also sell a humidity controller. Different cheeses need different humidities so it might be easier to make microclimates with ventilated boxes kept dry or moist depending on the cheese.

Mould Ripening

In an ideal world, we'd have four separate caves for blue cheeses, Bries and Camemberts, rind washed cheeses and all the others. In real life boxing the different types helps prevent cross contamination and vacuum packing is very convenient for non-mouldy cheeses. Mould ripened cheeses need oxygen so vacuum packing is not a good idea.

Cheese Types

Lactic - Cheese made by adding acid to the milk and very little or no rennet. Alternatively bacteria can be used to acidify the cheese.

Whey - Cheese curds made by adding acid to very hot whey or milk. For example Ricotta.

Brown - Whey is reduced by boiling to caramelise the milk sugars. Strictly speaking this is not cheese.

Rennet - Cheese made by adding rennet to the milk.

Junket cheese has no bacteria or moulds. It's bland and good for flavoured sweetened deserts.

Junket is a dilute form of rennet and not ideal for cheese making.

Most pressed and matured cheeses are of the rennet type.

Maturation relies on the action of bacteria and/or moulds.

Curdle - Separate milk into curds and whey. See Rennet.

Acid - Use citric acid, lemon juice or vinegar. Hotter milk curdles faster. Never boil milk.

Culture - Use a bacterial culture to acidify the milk.

Clabber

Allow raw/unpasteurised milk to turn sour from naturally occurring bacteria in the milk.

Pasteurised milk will not work. It'll just "go off" and be nasty.

Using kefir starter with pasteurised milk is an approximation to clabbering.

Curds

The treatment of the curds after splitting the milk has a dramatic effect on the final cheese produced.

Cutting, heat, stirring, resting and salting change the curds. Mozzarella requires heating and stretching.

Some recipes wash the curds. Whey is discarded and replaced with water to reduce the acidity.

Very gentle treatment is usually best.

I once made rubber ball bearings by stirring too much. These curds would not knit together if pressed.

Curds made at a high temperature will not cave ripen because the bacteria are killed by the heat.

Enzymes

Rennet

Separate milk into curds and whey.

Works above 30°C.

Fastest from 40°C to 43°C but this is too warm for most cheeses.

Use one drop in 4 litres for a soft cheese like chèvre.

Use 2.5 grams in 4 litres for a hard cheese.

Dilute or dissolve tablet rennet in 50 grams of cooled boiled water.

If you have double strength rennet, remember to use half the amount.

Stir with an up and down motion for no more than one minute.

Lipase

An enzyme used to break down milk fats.

Gives characteristic sharp tastes, aromas and velvety textures to Italian style cheeses.

Old milk contains more lipase and may taste rancid.

Pasteurised milk might need a lipase boost.

Adding lipase to cows' milk makes it more goaty.

Don't use too much. People report the cheese smells of baby puke!

Milk - Desirability ranking ...

GOOD

Raw - Not Pasteurised. Not homogenised. The best for cheese making. Local laws might prohibit sales.

Raw - Not Pasteurised. Homogenised.

Pasteurised - Not homogenised. Add CaCl2

Pasteurised - Homogenised. Add CaCl2. This is the commonest supermarket milk and it's fine for cheese making.

BAD

Rennet will not work properly.

Ultra-Filtered

This process alters the behaviour of rennet and cheese ripening.

Fresh cheeses from whole milk might be successful.

Avoid for ripened cheeses.

Versions marketed as energy drinks no longer contain what's needed for cheese. AVOID!

High temperature pasteurised

Similar to UHT below ...

Ultra-Pasteurised or UHT

Rennet will not set UHT milk.

You can make cheeses by adding acid to milk.

Allow the milk to curdle and separate the whey.

Paneer, Quark, Queso Blanco and Ricotta are possibilities.

Expect less yield and inferior results.

Moulds

Moulds need oxygen to grow. Use a humid ventilated box.

Avoid vacuum packing because it kills the these moulds.

WHITE

Geotrichum candidum - White mould. Mushroomy flavour. Reduces skin slip.

Penicillium candidum - White mould. Bloomy rind on Brie, Camembert, etc.

If white mould forms very fast in less than a week, the ageing area might be too warm.

Skin slip (a melted layer under the white mould rind) is more likely with fast mould development.

When mould begins to form, move the cheese to a cooler place.

Harmless pink mould indicates a too humid environment.

Brown or light brown mould indicates a too low humidity environment.

BLUE

Penicillium roquforti - Blue in mould in Roquefort, Stilton, Danish blue, Cabrales,etc.

Penicillium glaucum - Like roquforti but milder. Gorgonzola etc.

Ripen the cheese in a warm damp box until the blue mould forms.

Excessive humidity encouraged brevibacterium linens and maked the cheese very smelly.

Pierce the cheese all over and move it to a cooler place.

Once it's ripe enough, move to a normal fridge.

Moulds and Bacteria on a budget

Use rind shavings liquidised in milk and sieve out the lumps.

This method carries a slightly higher contamination risk compared with buying the dried cultures. I've had no failures and many really tasty cheeses.

White mould can be harvested from the rinds of Camembert, Brie, etc. to make similar cheeses.

Blue mould can be harvested from the rinds or veins of any blue cheese to make similar cheeses.

Blue mould grows well on sourdough toast and can be frozen for later use.

Red bacteria Brevibacterium linens is present on human skin. A vinegar hand spray helps to prevent transfer to the cheese.

Red bacteria for stinky cheeses can be encouraged by rind washing with dilute brine every day or two.

Frozen cubes can be stored. Add bacteria and/or moulds to the milk and divert some into ice cube bags. Culture for 12 hours, then freeze.

Mozzarella

This is quite tricky to make. The pH has to be just right if the curds are going to stretch. Beginners without a pH meter often fail with this cheese and succeed, only by luck.

pH

Melting and stretching: Aim for a pH of 5.2 to 5.4. As the ripening curds and whey approach pH 5.4, drain the whey and add the salt. Washing the curds slows the pH drop. Getting this right is not easy and failed Mozzarella is a common problem.

Squeaky cheese: over a one hour period slowly warm and stir the curds to 38.5°C and hold this temperature until the pH falls to 6.2 or 6.1. Drain and salt. The squeak only lasts a day or so.

Pressing Cheese

Forget weights. Watch the whey instead.

Normally I'm all in favour of doing the sums/maths but not in this case.

The pressing weight in the recipe does guide you.

Soft cheeses have a mid-range pressing weight.

Hard cheeses might go up to the limit of your press.

Nearly every recipe starts with a low pressure and ramps it up.

So start with the smallest weight that causes clear whey to drip out of your press.

Gradually ramp up the pressure/weight and turn the wheel over now and then

Always look for clear whey dripping.

If cheese starts extruding, the pressure is too high.

If there is no slow dripping, the pressure is too low or perhaps the pressing is complete.

Don't apply too much pressure too soon.

This might trap whey in the core of the cheese, cause drying problems later and perhaps cause bitterness.

For the last press, for a smooth rind, discard the cheese cloth

Invert the wheel and press a final time at a high pressure.

Pressing curds works better if the curds are still warm.

Look for clear or slightly cloudy whey.

If the draining whey is cheesy, the pressure is too high.

Fatty cheeses might expel fatty whey. This is not a problem.

Once whey stops draining, further pressing is not useful.

If your wheel is full of mechanical holes, this is not a problem but next

time try pressing with warmer curds at a higher final pressure and perhaps for longer.

Mechanical holes are normal for some cheeses.

Extra time in the press might help the curds to knit together.

Add curds to your mould in one step.

Adding extra curds later forms layers that might split the cheese.

Curds are less likely to glue to the cheesecloth if it is more acidic than the curds.

Wet the cheesecloth with vinegar or ripe whey before pressing.

Whey - The liquid remaining after milk has been curdled and strained.

Acid or Sour

Use a bacterial culture to separate the milk.

This takes up to 24 hours.

Or use citric acid, lemon juice, vinegar or another acid.

Acid whey is low in fat and high in lactic acid.

The cheese will be higher in fat and lower in lactic acid.

This whey is not suitable for making ricotta.

Sweet

Use rennet and sometimes rennet with a culture to make sweet whey.

This takes up to an an hour or longer if a culture is included.

Unripe sweet whey is high in fat and low in lactic acid.

The cheese will be lower in fat and higher in lactic acid.

Use sweet whey to make Ricotta. Use it fresh before the bacteria have a chance to acidify the whey.

Uses for Whey

Ricotta from sweet whey. The yield is too small from sour whey.

Smoothies.

Replace water in baking bread and cakes.

Fermented vegetables but this is disputed. Veg' already contains all the bacteria needed.

Make porridge.

Brine meats.

Flavour soups and stocks.

Pressure cook a chicken in whey and reduce the liquid to a thick yummy gravy.

Ham and pea soup made with whey is wonderful.

Boil down the whey to make a tasty caramel (no added sugar) - e.g. Prim, Brunost, Mynost, Gjeitost

Make caramel with added sugar and/or cream by reducing the whey.

Dilute the whey 50:50 and use it occasionally to water the garden.

Defects and Unexpected Holes in Cheese

Please read the LTMC safety documents and FAQ at these links ...

The photos below show some classic defects. Beware of cheeses with more than one problem.

Late Blow

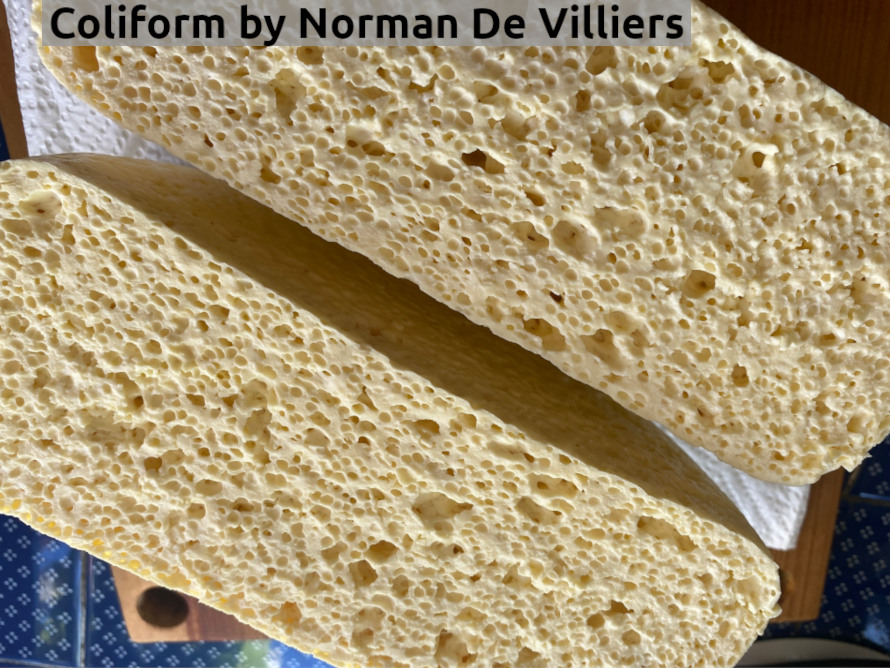

Coliform Contamination

Mechanical Holes

These are harmless irregularly shaped gaps in the curds that occur when pressing.

Many commercial cheeses have this feature.

Mechanical holes really don't deserve the "defect" label.

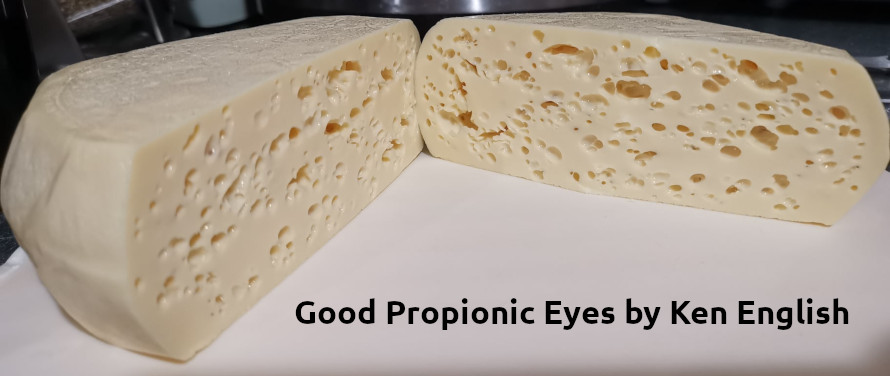

Propionibacterium shermanii

This is not a defect. This cheese culture contains bacteria that makes eyes or holes by blowing bubbles of carbon dioxide.

Raw milk might contain this, especially if you live near an Alpine mountain meadow. If you get these holes at the right time, be very happy!

Yeast

This is not caused by bread or alcohol yeast. There are hundreds of other wild yeasts in the environment. Some can ruin a cheese.